Are the accounts of the resurrection contradictory?

If the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth from the dead is the most important and foundational truth of the Christian faith, how come the New Testament accounts of the resurrection and Jesus’ appearances are so contradictory? That is a relatively widespread response in atheist/apologetic circles, and I think amongst Muslim critics of the Christian faith. I think this one, in a blog raising objections to Christian faith, is a good example:

How many days did Jesus teach after his resurrection? Most Christians know that “He appeared to them over a period of forty days” (Acts 1:3). But the supposed author of that book wrote elsewhere that he ascended into heaven the same day as the resurrection (Luke 24:51).

When Jesus died, did an earthquake open the graves of many people, who walked around Jerusalem and were seen by many? Only Matthew reports this remarkable event. It’s hard to imagine any reliable version of the story omitting this zombie apocalypse.

The different accounts of the resurrection are full of contradictions like this. They can’t even agree on whether Jesus was crucified on the day before Passover (John) or the day after (the other gospels) … [a list of other contradictions]

Many Christians cite the resurrection as the most important historical claim that the Bible makes. If the resurrection is true, they argue, the gospel message must be taken seriously. I’ll agree with that. But how reliable is an account riddled with these contradictions?

It might be argued that, for Christians, the Easter Octave that we are in is a time for celebrating the truth of the resurrection, and not a time for nit-picking. But it seems that there are certainly questions out there, and there might be questions ‘in here’ too! In my experience, Bible-reading Christians have more questions than we often allow for! One of the last comments on the blog says:

The best way to lose faith in the Bible is to actually read the book, viewing all the absurdities, atrocities and contradictions. No wonder many Christians have not, or that non-believers show greater knowledge of it.

But actually reading the Bible simpliciter is not enough — at least, if we read it in the way we would read a car maintenance manual, or a modern novel, or a newspaper report — which is how many of the people in the blog discussion appear to be doing. David Cavanagh, of the Salvation Army in Italy, comments online:

Some “conservative” or “traditional” Christians believe that Scripture is inspired and therefore must be historically (and, in some cases, scientifically) “accurate” or “true”.

Some “liberal” or “revisionist” Christians, recognising that there is much in Scripture which is difficult to square with “history” and “science”, argue that the Bible cannot be the definitive guide to Christian faith and life.

Both fail to recognise that they are imposing anachronistic and alien criteria of historiographical and scientific “accuracy” and “truth” onto ancient texts which function according to different dynamics

Jesus performed many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not recorded in this book … Jesus did many other things as well. If every one of them were written down, I suppose that even the whole world would not have room for the books that would be written. (John 20.30, 21.25).

I cannot make my mind up whether this has been written with a sense of excitement at the publishing possibilities, or with a weary sigh at the effort of writing! But the point is that in any of the gospels, and even in them all put together, we do not have a full account of Jesus’ ministry, nor a mention of all the people that he engaged with. Hence it is perfectly possible for Luke to record Paul recalling words of Jesus that we do not have in the gospels (Acts 20.35), and that the naming of individuals relates to their importance in the early Christian community (according to the argument of Richard Bauckham). Notice, for example, that John 20.1 only mentions Mary Magdalene, but that her report to the disciples in the next verse says ‘We do not know where they have taken him’, making it clear that, whilst she alone is mentioned, she is not alone.

Thirdly, we need to recognise that the gospel writers are less concerned with chronology than we are, and are content to rearrange elements of their stories in order to make a theological point or tell us what they think the significance is of an action or teaching of Jesus. The most glaring example is Matthew’s ‘Sermon on the Mount’, which wasn’t a sermon and didn’t happen on a mountain, but it is something that we find everywhere. Surely Luke’s ‘Journey to Jerusalem’ motif from Luke 9.51 onwards is not there to tell us exactly when Jesus taught what, but to show (especially to his Gentile readers) the central importance of Jerusalem to Jesus’ ministry.

Bearing these things in mind, is it still possible to believe that the different accounts (not just in the gospels, but also in Acts, and Paul’s account in 1 Cor 15) are derived from a consistent series of actual events, rather than being ‘legendary’? If there are irreconcilable differences, then I think we need to take the challenge above seriously — but, as I have demonstrated in relation to the ‘most difficult contradiction in the New Testament’, the two accounts of Judas’ death in Matt 27.3–8 and Acts 1.18, supposed contradictions are often (under careful scrutiny) not what they appear to be.

There is a good attempt to set out the underlying events (a better term than ‘harmonise’) on this Bible questions website, based on the work of Gary Habermas and Michael Licona:

- Jesus is buried, as several women watch (Matthew 27:57-61; Mark 15:42-47; Luke 23:50-56; John 19:38-42).

- The tomb is sealed and a guard is set (Matthew 27:62-66).

- At least 3 women, including Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome, prepare spices to go to the tomb (Matthew 28:1; Mark 16:1).

- An angel descends from heaven, rolls the stone away, and sits on it. There is an earthquake, and the guards faint (Matthew 28:2-4).

- The women arrive at the tomb and find it empty. Mary Magdalene leaves the other women there and runs to tell the disciples (John 20:1-2).

- The women still at the tomb see two angels who tell them that Jesus is risen and who instruct them to tell the disciples to go to Galilee (Matthew 28:5-7; Mark 16:2-8; Luke 24:1-8).

- The women leave to bring the news to the disciples (Matthew 28:8).

- The guards, having roused themselves, report the empty tomb to the authorities, who bribe the guards to say the body was stolen (Matthew 28:11-15).

- Mary the mother of James and the other women, on their way to find the disciples, see Jesus (Matthew 28:9-10).

- The women relate what they have seen and heard to the disciples (Luke 24:9-11).

- Peter and John run to the tomb, see that it is empty, and find the grave clothes (Luke 24:12; John 20:2-10).

- Mary Magdalene returns to the tomb. She sees the angels, and then she sees Jesus (John 20:11-18).

- Later the same day, Jesus appears to Peter (Luke 24:34; 1 Corinthians 15:5).

- Still on the same day, Jesus appears to Cleopas and another disciple on their way to Emmaus (Luke 24:13-32).

- That evening, the two disciples report the event to the Eleven in Jerusalem (Luke 24:32-35).

- Jesus appears to ten disciples — Thomas is missing (Luke 24:36-43; John 20:19-25).

- Jesus appears to all eleven disciples — Thomas included (John 20:26-31).

- Jesus appears to seven disciples by the Sea of Galilee (John 21:1-25).

- Jesus appears to about 500 disciples in Galilee (1 Corinthians 15:6).

- Jesus appears to his half-brother James (1 Corinthians 15:7).

- Jesus commissions his disciples (Matthew 28:16-20).

- Jesus teaches his disciples the Scriptures and promises to send the Holy Spirit (Luke 24:44-49; Acts 1:4-5).

- Jesus ascends into heaven (Luke 24:50-53; Acts 1:6-12).

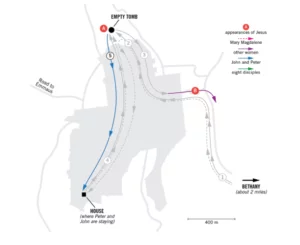

This matches the similar outline given by the late Michael Green in The Empty Cross of Jesus (first ed, p 122); a similar one on the fundamentalist website Answers in Genesis has a nice animated graphic map of Jerusalem, though unfortunately it uses the modern (rather than ancient) outline of the city, and assumes ‘Gordon’s Calvary’ and the Garden Tomb as the historic site, rather than the more probable site now marked by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. But points made about distances and journey times still stand. (See other variations here and, less convincingly, here.)

This matches the similar outline given by the late Michael Green in The Empty Cross of Jesus (first ed, p 122); a similar one on the fundamentalist website Answers in Genesis has a nice animated graphic map of Jerusalem, though unfortunately it uses the modern (rather than ancient) outline of the city, and assumes ‘Gordon’s Calvary’ and the Garden Tomb as the historic site, rather than the more probable site now marked by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. But points made about distances and journey times still stand. (See other variations here and, less convincingly, here.)

Out of this, there are some important and interesting things to note. The first (ironically) is the very marked diversity between the accounts. In most of the earlier episodes of the gospel narratives, we are able to distinguish between the ‘Synoptics’ (Matthew, Mark and Luke) who take a broadly similar approach (most often based on the narrative framework of Mark, which Matthew and Luke never agree against) and the quite different view of John. Within that, we note the ‘double tradition’ of Matthew and Luke, which has led to the belief in a lost written source ‘Q’ that they both drew on (though its existence is disputed). But in the resurrection narratives, all these groupings and relationships seem to disappear. This is the point in the story where, despite agreement on the central facts (which we will return to), each gospel writer appears to have both a distinct concern in communication and a distinct set of sources. For example, Matthew locates Jesus’ Great Commission to take the good news to the Gentiles in Galilee — what an apt setting — to signify the change from the earlier instruction in Matt 15.24 only to go to the ‘lost sheep of the House of Israel’. But Luke continues his focus on Jerusalem, and doesn’t make reference to Galilee appearances, whilst John includes both, though with a characteristically Jerusalem angle, which would fit the author of the gospel being the Jerusalemite ‘beloved disciple.’

The second thing to note is the inclusion, especially in Luke and John, of important personal details. Both the account of the appearance on the Emmaus Road in Luke 24 and the scene at the garden tomb in John 20 include numerous ‘personal realism’ details, which is what makes the stories so engaging and compelling to most readers. Alongside this, I have been struck with how little symbolism there is in the account of John 20; for example, why does the writer record that the ‘other disciple’ can run faster than Peter, and reaches the tomb first, only for Peter to then barge past him — unless that is how it happened? The account appears to make nothing significant or symbolic of this detail. If the gospel writers are indeed relying on different eye-witness testimony, then that fits well with the nature of the stories as we have them, and accounts well for the diversity of the accounts.

Thirdly, readers familiar with these stories might not have realised how well the stories fit with historical reality of the first century. Only the family tombs of the relatively wealthy would have disk-like round stones closing the entrance which need to be rolled away (and there are more and more examples of these being excavated year by year); the entrances are often quite low, so you would indeed need to stoop down to see the inside (John 20.5) and the space (unlike a modern ‘tomb’) can indeed be ‘entered’ (Mark 16.5). But you cannot see everything from the outside, so if there were heavenly beings at the head and the foot of the space where the body was laid (John 20.12), then you would not see both from the outside. And the dead were indeed wrapped with two different cloths, one wound round the body, and a separate one (the soudarion, John 20.7) around the head, which would be left in two, neat, folded piles were the body to be miraculously removed. (I am surprised to find that very many modern readers still do not understand that significance of this detail, and why it led the ‘other disciple’ to ‘believe’ that something extraordinary had happened.) These historical details connect with other correlations, including those related to the trial, death and burial of Jesus, which indicate actual historical events as the common source.

But all these diverse perspectives appear to circle around a series of core facts, on which all the accounts seem to agree:

- That women first went to the tomb early on the Sunday morning;

- That the stone had been rolled away, and that the tomb was empty;

- That there were angelic beings present;

- That some male disciples came to the tomb in response to the report of the women, and found the same;

- That the consistent response of all the disciples (both men and women) was a mixture of wonder, confusion, and fear;

- That Jesus himself appear to a wide range of people on different occasions;

- That the people he met consistently failed to recognise him at first, quite possibly as a result of their lack of expectation;

- That he was both bodily, in the sense that he could be touched, and he ate, and yet he was also transformed, in that he could appear and disappear at will;

- That after a period of time, he was taken up to heaven.

If there were contradictions in these central events — or if the portrayal of the disciples was less unflattering, or the first witnesses being women was less embarrassing — then I think we would have grounds to consider the accounts ‘legendary’. As it is, I think the criticisms that we started with are based on false expectations, and fail to note the remarkable agreements of the very diverse accounts.

(Previously published the last two years but, by all accounts, worth repeating again!)

About the author …

- Ian Paul: theologian, author, speaker, academic consultant. Adjunct Professor, Fuller Theological Seminary; Associate Minister, St Nic’s, Nottingham; Managing Editor, Grove Books; member of General Synod. Mac user; chocoholic. Tweets at @psephizo